Afraid of the Dark

- Mark Robinson

- Mar 6, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Apr 15, 2023

“For 13 months, I was the Jackie Robinson of television,” wrote Nat King Cole in a revealing 1958 article for Ebony magazine entitled “Why I quit my TV show.” “After a trail-blazing year that shattered all the old bug-a-boos about Negroes on TV, I found myself standing there with the bat on my shoulder. But the men who dictate what Americans see and hear didn’t want to play ball.”

That was more than sixty years ago. So it is understandable that many people might not know all that much about the legendary singer, Nat King Cole. I’m happy to fill in a few blanks.

Nat King Cole began his professional career in the 1930s as the pianist and leader of the Nat King Cole Trio. One night, a club owner told Nat, “The vocalist didn’t show tonight, so you gotta sing.”

Nat protested, “But I don’t sing. I’m a piano player.”

The club owner insisted, “You want to get paid, tonight, you sing.” And thus, launched one of the most “unforgettable” voices in jazz.

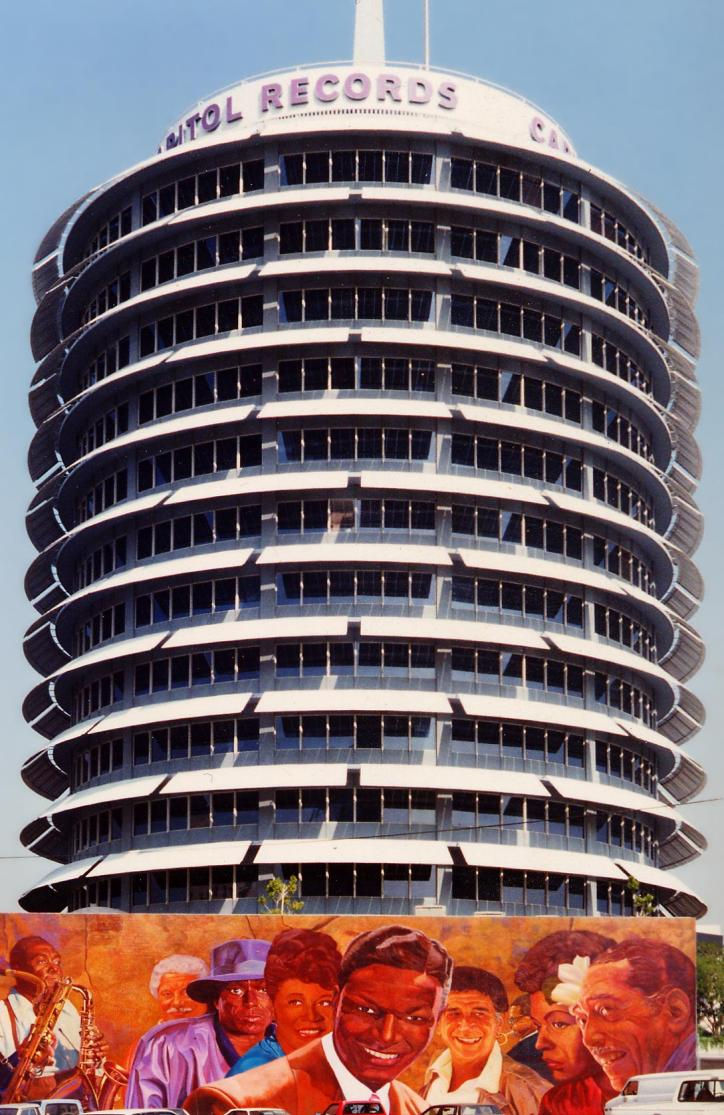

In 1937, Nat wrote and sold his first song, “Straighten up and fly right”, which became a huge hit and a staple of nightclubs in the late 1930s and 1940s. In 1942, Nat King Cole signed with Capitol Records, a fledgling new label at the time. Nat’s two-decade run of chart-topping hits turned Capitol Records into a recording empire and an iconic Hollywood landmark known as “The house that Nat built.”

Nat’s songs included “Unforgettable”, “Smile”, “Mona Lisa”, “Route 66”, “Nature Boy”, and “When I Fall In Love”. It would simply take too long to list all of his big hits.

From 1938 – 1965, Nat released more than 100 Top Ten singles and two dozen Top Ten albums. That’s more than Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston combined. No one has matched his record. Nat King Cole is in the Grammy Hall of Fame, the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Only Lennon and McCartney can make that claim. And since his death in 1965, over 100 more Nat King Cole albums have been released. Five were gold records; another five were platinum. Only Elvis can make that claim.

In 1956, Nat Cole was one of the most successful entertainers in the world. Of ANY color. His gentle, romantic style of singing endeared him to millions, and his record sales were phenomenal. There was every reason to believe that a TV show starring Nat King Cole would be a huge hit. Nat saw the potential for something more than just entertainment success. “It could be a turning point,” he said, “so that Negroes may be featured regularly on television.”

But this was 1956, and Civil Rights was very much an active battleground. Many, especially in the media establishment, did not feel America was ready for Negroes to host their own TV programs, no matter who that Negro was. Nat originally signed a contract with CBS, but the network got cold feet, and the deal fell through. Later in the year, NBC stepped forward, and on November 5, 1956, The Nat King Cole Show was on the air.

The show featured some of the biggest performers of the time, including Ella Fitzgerald, Peggy Lee, Sammy Davis Jr., Tony Bennett, Count Basie, and Harry Belafonte. The orchestra was conducted by Nelson Riddle. It was the best entertainment on TV. There was just one small problem. This was a network TV show that did not have a single national advertiser. Not one single advertising agency was willing to buy national airtime on the show for any of their clients. National airtime meant that the ads would run in southern markets, and advertisers were afraid of white southern boycotts of their products. A representative of Max Factor cosmetics, a potential sponsor for the program, claimed that a negro couldn’t sell lipstick for them. Cole was angered by the comment. “What do they think we use?” he asked. “Chalk? Congo paint?”

The result was that NBC was forced to create a patchwork of local sponsors in just a handful of key markets. Rheingold Beer advertised in New York. Gallo Wines and Colgate Toothpaste in Los Angeles. And Coca-Cola in Houston. It was not uncommon for the show to air without any commercials. Advertising sponsorship is the lifeblood of television, but the Nat King Cole Show was getting none of it. The show was never able to turn a profit. Despite the losses they suffered, NBC kept the show on the air for a second season. Nat even used his own money to underwrite expenses. Finally, after 64 weeks, Nat King Cole made the decision to cancel the show.

In the Ebony magazine article that served as a postmortem on the show, Cole praised NBC for its good faith efforts. “The network supported this show from the beginning,” he said. “From Mr. Sarnoff on down, they tried to sell it to agencies. They could have dropped it after the first thirteen weeks.”

Nat King Cole placed the blame squarely on the advertising industry. “Madison Avenue,” Cole said, “is afraid of the dark.”

But the advertising agencies of Madison Avenue were not at all happy being called out publicly as racist, nor were their clients. Nat Cole’s remarks in a national magazine were a cold slap in the face by an uppity Negro. The men of Madison Avenue, the men in the grey flannel suits, were the kingmakers, the taste-makers. They would see to it that they had the last word in this feud. And they were quite capable of showing their venal, petty, and vengeful side to do it.

The late 1950s and early 1960s were the heyday of celebrity endorsement advertising. Everyone from John Wayne to Jack Webb and Lucille Ball were making lots of extra bucks plugging products. Celebrity endorsers and the products they shilled were so inextricably intertwined that you had TV shows like the Bob Hope Texaco Star Theater. All the big celebrities were cashing in.

Except for Nat King Cole. On Madison Avenue, Nat’s name wasn’t even whispered. Despite out-shining and out-selling virtually every other performer, Nat Cole could not get the time of day from any advertising agency. Madison Avenue got the last word, after all.

Comments